October is “Todd Samara Month”

—and a November Auction Preview

Self Portrait

For more than 30 years, Todd Samara lived and painted in Kingston’s Rondout neighborhood, translating its hilly streets, tight rows of 19th-century gable-roofed houses, sailboats, bridges and panoramic river and mountain views into poetic visions characterized by simplified, textured forms and rich, glowing color. To preserve his legacy, two Kingston galleries are hosting exhibitions of his work in October, which will precede an auction of more than 300 of his paintings in November.

The exhibitions, at The Lace Mill, located at 165 Cornell Street, and The Storefront Gallery, located at 93 Broadway, will open on Saturday, October 6, from 5 to 8 pm. Three businesses with Samara’s works on their walls—Dolce, at 27 Broadway; A.I.R. Studio Gallery, at 71 O’Neil; and Tony’s Pizzeria, 582 Broadway, which has a couple of stunning murals—will also be open to visitors during the 1st Saturday gallery openings on October 6. The map of gallery locations, which is printed by the Kingston Midtown Arts District each 1st Saturday, will also show the location of three outdoor murals by Samara, two of which grace the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Download the map.

“We’re celebrating October as Todd Samara month,” said Nancy Donskoj, owner of The Storefront Gallery and a friend of the artist. “We want to make sure Todd’s important legacy is not forgotten.” She noted that many of the scenes painted by him will be recognizable to long-time residents, given that the subjects include a neighborhood laundry mat, local bars, a schoolroom, a friend’s basement and even the late City of Kingston Mayor T.R. Gallo’s funeral. Collectively, Samara’s work is a compendium of the working-class culture and artists’ community of downtown Kingston in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Samara, who is currently unwell and residing in a nursing facility, was described as “the quintessential local artist” by American Artist, which published an eight-page spread about him in its July/August 2010 issue. He exhibited at numerous galleries in Kingston and sold his paintings at local restaurants, real estate offices and bookstores. Seemingly indifferent to the pressures of the art world, he would sometimes stroll down to T. R. Gallo Park with a cache of small works, selling them to passersby for $10 or $20.

He was born in Brooklyn in 1943, grew up in Queens and, upon graduating from high school, joined the U.S. Navy as a reservist and served on an aircraft carrier stationed in Europe and the Caribbean. He painted portraits of the other sailors as well as the ship’s signs and insignias and a mural of Moby Dick in the officer’s lobby, works that earned him “a generous leave” at each port, he recalled in a 2010 interview. After quitting the Navy in 1969, he rented out two storefronts in Queens as a studio and eventually moved to Rosendale, where he bartended and painted murals and portraits of the town’s counterculture residents. At age 35, he began studying art at SUNY New Paltz, eventually earning a BFA.

In the late 1990s, Samara resided in a steel-hulled, turquoise-hued boat moored at Kingston’s Hideaway Marina, spending winters in a shack onshore. After meeting his late partner, Leslie Miller, a ceramist, in 2001, the couple rented a small, 19th-century house on Hone Street, where Todd painted in a low-ceilinged, crowded studio in the basement.

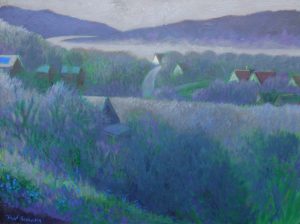

He painted from memory, frequently walking the streets of Rondout for inspiration. Leslie’s tragic death in 2009 caused a shift in his palette to more somber colors. Some of the best of these dreamy, often otherworldly landscapes of Rondout, whose luminosity is achieved partly by juxtaposing warm and cool hues and complementary colors, will be on view at The Storefront Gallery.

Samara also painted figures and portraits, including depictions of his musician friends, cats, and interiors; some of the paintings of his studio suggest a cubistic space due to shifts in perspective from the many paintings-within-the painting. The Lace Mill exhibition, which is curated by Chris Gonyea, an artist and former gallery owner who is organizing and conducting the auction, will consist of an overview of all these categories of Samara’s work, loosely arranged chronologically, from his student work to paintings from a couple of years ago. Among the highlights will be some knock-out landscapes and a series of self-portraits (several of which, including a portrait of the artist in white made with a palette knife, show the strong influence of late 19th-and early 20th-century French painting).

“The exhibitions will be a preview of the best stuff,” said Gonyea, who has been cataloging the hundreds of works. The date and location for the November auction will be announced in a couple of weeks. “The auction will be ‘no reserve,’ meaning that there will be no minimum price set,” he added.

All of the proceeds from the auctioned art will be donated to a scholarship fund benefiting local emerging artists. The fund will be administered by Kingston Midtown Arts District (MAD) and the Kingston Arts Commission.

“In trying to decide how best to deal with all of Todd’s artwork after he went into long-term care, his friend, Jay Bedient, suggested the possibility of an auction and using the proceeds towards a scholarship of some kind,” explained Tom Samara, Todd’s brother, who resides in Bordentown, New Jersey. “Since Todd and most of his work had such a connection to Kingston and the people there, we, his family, felt a scholarship would be a great way to keep Todd’s presence alive in the art community and to offer a little help to other artists.”

For more information, please contact Nancy Donskoj at 845-514-3998 or visit the Facebook page, www.Facebook.com/SamaraProject or follow @SamaraProject on Twitter.

“Painting never dies. It just keeps moving. You get past the madness and through the training of meditation, see the truth of the universe.” –Todd Samara

Click any photo to start a slideshow.

Todd Samara/Kingston Times

by Lynn Woods

May 14, 2013

Some places are inextricably linked with the artists who painted them. Fin de siècle Paris will forever be linked to the Impressionists and especially, the paintings of Manet, the cornfields and orchards of Arles with Van Gogh, Mont Sainte-Victoire in southern France with Cezanne, Mount Fuji with Hokusai, and Depression-era Main Streets with the matter-of-fact paintings of Edward Hopper. Similarly, Kingston’s Rondout will forever be associated with the paintings of Todd Samara.

For 30 years, the 70-year-old artist has painted Rondout’s rows of gable-roofed houses, its panoramic river and mountain views, its boats, hilly streets, and people, doing the wash in laundry mats, hanging out in bars, playing in the schoolyards. Samara, who works from memory, has translated this subject matter into a language of simplified, textured forms and rich color, ranging from fauve-like intensity to subtle nuance; even his nocturnes glow with luminous blues and lavenders.

Anyone who knows Kingston knows a Samara when they see it. His murals adorn various corners of the city and his paintings are on more or less permanent display at Half Moon Books and Hudson Coffee Traders Uptown and Mint and Dolce in the Rondout. His style is distinctive, yet, when I sat down in the rotunda of the Hudson Coffee Traders earlier this week, it took me a moment to recognize the paintings surrounding me as his work, due to their starkness. They were radically simplified: like Giorgio Morandi’s bottles, houses have been reduced to their bare, geometric essence, as color shapes, accented with perhaps a single window. A scene is reduced to a few buildings, a patch of sky, and a shadow, with the contrasts in some paintings intensified. The paintings are devoid of people, heightening the sense of interiority and evoking primal states of emotion.

“Less is more,” said Samara, in a recent interview at his cozy Rondout home, which still contains its 1950s kitchen appliances. “I’m playing with colors and shapes. Each triangle or square connects to the one next to it. Maybe they’re on the same plane; you can’t always tell the background from the foreground. I’m playing with metaphysics. I’m trying to meditate and maintain the focus by thinking of no thing. I’m leery of that impressionist thing, which has way too many things going on at once. It’s like entertainment. Now I’m trying to be less romantic, for a certain quietness.”

Samara works out of a small studio in the basement of his 19th-century house. He also paints in his bedroom: When he wakes up in the morning, the first thing he does is to scoot over to a small table near his bed in a castor-wheeled stool and make one or two pictures on paper using cray-pas. “I don’t think,” he said. “It’s very spontaneous.” He then scoots over to another table and works on a small acrylic painting—or, as he has been doing of late, to a third table where he works on small panoramas using a brush dipped in ink. Sometimes he’ll put a bunch of these small works on paper in a folder and go down to Gallo Park, where he’ll sell them to passers-by for $10 or $20. His paintings and the ceramic works of Leslie Miller, his late partner, cover the walls, and more paintings are stacked against walls and piled up in corners.

Samara received national recognition when he was featured in the July-August 2010 issue of American Artist Magazine. The article came about after the writer discovered Samara’s paintings hanging in Dolce while on a visit to Kingston. The article sparked inquiries on his website, which his sister manages for him (he doesn’t have a computer). Though he was glad for the coverage and definitely would like to sell more paintings, which he relies on to pay his rent, supplemented by odd jobs and helping out a carpenter artist friend, he has no inclination to show his work outside of the area. Samara doesn’t drive, and he likes to keep things simple. When the owner of the house next door, where he and Miller were living in an apartment, offered to sell them the building for $10,000, Samara declined. “I don’t want to own anything. I hear about the problems from those who do.”

Samara has always marched to the beat of a different drummer. “I was against the rules because I couldn’t follow them,” he said, noting he rebelled against authority while growing up in Queens. Lately, though, he’s been going against his instincts. He’s taking lessons on the clarinet and learning to read music. “I’m breaking through that wall so I can create any feeling I want,” he said. Why clarinet? “It’s a romantic thing. I grew up hearing the clarinet. My parents were great dancers and went out every night. Music is like meditation. It puts you in another space. It’s like painting, in that I’m trying to put the feeling down.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1943, Samara made his first painting when he was 14, using the easel and paints of his father, a printer and frustrated artist. His father also introduced him to jazz and alcohol, taking his son to the Five Spot in lower Manhattan, where Dave Brubeck and other greats played. Samara has a photographic memory for images—he can look at something and then paint it from his head—but that didn’t help much in school, where he had trouble reading due to his dyslexia. “I was a cute red-headed kid with freckles, and the teachers felt sorry for me, so they kept passing me with 65s,” he recalled. He worked at Orbach’s, a clothing store across from the Empire State Building, instead of going to school some days as part of a special work/study program.

After graduating from high school he joined the Navy as a reservist and served on an aircraft carrier, traveling to the Caribbean and Europe. His first job was parking the planes, but “I was such a klutz, always banging myself on the wings, that they put me in the gear locker room,” where he handed out the tools. One day he found a big piece of wood and some red and white lead paint and painted the nude bust of a woman. Everyone liked it, and he started doing sketches and paintings based on photographs for the other sailors. He painted all the insignias and a large sign that read “Accidents do not happen, they are caused.” After he painted a mural of Moby Dick in the officer’s lobby, Samara enjoyed generous leave privileges when the boat was in port, hanging out in bars.

He quit the Navy in 1969 and moved back to Queens, renting two storefronts for $200 a month, which served as his studio, art gallery, and crash pad. He sold some work and attracted five students, “bored housewives who came over with a jug of wine and cheese. We discussed the arts.”

One day a couple came in who “clued me into Salvador Dali.” When they moved to Rocky Point, Long Island, where they opened an art gallery, Samara followed, renting space in the gallery and working as a bartender in the bar next door. After hitchhiking up to Rosendale to visit a friend who was living at Mohonk, Samara left Long Island for the former cement manufacturing town and worked as a bartender at The Well. His work at the time was influenced by the Mexican muralists and Cubism. He painted a handsome mural on the façade with curling flowers and a portrait of the bar’s owner, Uncle Willie, wearing a crown and cloak. He painted portraits of the ragamuffin clientele, who lived upstairs or in the nearby Astoria Hotel. One stoned-out patron freaked out upon viewing his portrait, which depicted his rolling, frenetic eyes and onyx necklace. “My client said ‘I see death’ and became a Christian because of the painting,” Samara recalled.

A friend convinced Samara to enroll at SUNY-New Paltz. However, “they wouldn’t let me in because of my low high-school average” even though he was an accomplished artist. Based on the mistaken impression by an administrator that Samara was Japanese in a phone conversation, he was nonetheless accepted into a special Educational Opportunity Program designed for minorities. Between the monthly subsidy he received in that program and grant money, “I made a few thousand a year,” which was sheer profit since he didn’t pay for housing, living in the free studio provided by the school. It was against the rules, but when a security guard broke in one night and discovered Samara living there, the artist convinced him to let him stay. “I said, ‘I’m a crazy artist and can only paint at night.’” Eventually bought a wooden dory for $200 and lived on it in Eddyville, hitchhiking every day to New Paltz.

“I was 35 years old, and I thought I could probably stay there the rest of my life,” he said. But all good things must pass, and after five years Samara graduated with a BFA. He had some good art teachers, especially one professor who helped him “look at everything as if it were alive.”

He bought a steel-hulled boat and lived at the Hideaway Marina for five years, where he worked, migrating to a shack on the property in the cold winter months. After meeting Miller in 2001, the two moved into a series of apartments, eventually ending up in the house where he lives now. Miller was diagnosed with cancer in 2004, which seemed to be cured after surgery but then returned. She spent time at home reading and writing poetry and did exhaustive Internet searches of alternative treatments. It was a difficult time. One day in 2004, “I bought a quart of Budweiser and a pack of cigarettes and knew I had to make a decision to go or stay,” Samara said. After that, he never drank or smoked again. “I know if I had stayed that way I would have killed myself. I was never addicted, but I couldn’t afford to do it and didn’t like all the rules. I kind of missed the madness of it all. But my attitude changed. I was not so upset as before.”

He and Miller started going to weekly qi dong classes at Benedictine, which Samara still attends. Stylistically, his paintings became darker, more somber. Miller died in 2009. The sign with both of their names still hangs near the front door, and her ceramic plates, sculpture and painted furniture maintains her presence in the house.

Having completed the series of austere, abstracted paintings for Hudson Coffee Traders, which will be on view through June, Samara said his style is shifting again, back to an energetic, impressionistic stroke. “I’m adding texture,” he said. “Painting never dies. It just keeps moving. You get past the madness and through the training of meditation, see the truth of the universe.”